In the climate change causation chain—from emissions, to greenhouse gas concentrations, to temperature change, to environmental impacts—the impacts are often the most difficult part of the chain to grasp. A major report by the UK Met Office Hadley Centre released at the beginning of December is, therefore, especially welcome, particularly as it incorporates 24 individual country studies (here) on climate impacts.

For the UK, the Met Office makes the following projection:

The UK is projected to experience temperature increases of up to around 3°C in the south and 2.5°C further north. The agreement between models is moderate in the south of the UK and low further north.

To start putting this in context, the 3C number above is by the year 2100 and is the change over the 30 year average for the 1960-1990 period (which is used as the baseline). For rainfall, we see this summary statement:

Europe shows a strong contrast in projected precipitation changes, with large decreases in the south and large increases in the north. The UK falls towards the northern region with generally increasing precipitation, with projected increases of up to 10%, though some southern parts of the UK may experience decreases of up to 5%. There is generally good agreement between ensemble members over the north of UK, but moderate agreement further south, indicating uncertainty in the position of the transition zone between increasing and decreasing precipitation over Europe.

The report then goes on to consider a number of sectors in turn: crop yields, food security, water stress and drought, pluvial flooding (rainfall saturation), fluvial flooding (river related), cyclones (extreme winds) and coastal impacts.

With such a broad spectrum of topics to choose from, a journalist covering the report has ample opportunity to push their own particular agendas. This headline from the Guardian:

Met Office warns of UK climate risks: Britain will experience water shortages and flooding by the end of the century if temperatures are left unchecked, analysis shows

And this from the Daily Mail:

Global warming would BOOST Britain’s farm crops by 10pc

While this blog occasionally focuses on the distorted press coverage of climate change, this is not a topic I want to pursue today. Overall, I am more interested in trying to understand the risks that climate change poses to individuals and their families. In this vein, not one newspaper deemed it necessary to mention the critical assumption the Met Office made: namely, the emission path underpinning their climate impact forecasts. Change this premise and you change the projection. Accordingly, the emission path used by the Met Office, which is clearly stated in the report summary, needs to be highlighted.

For the A1B emissions scenario the UK is projected to experience temperature increases of up to around 3°C in the south and 2.5°C further north.

So the projections given by the Met Office are premised on the world following the A1B emissions scenario; if the world doesn’t follow this scenario, the Met Office’s projections are invalid.

The A1B scenario came out of a report entitled the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2000. These SRES scenarios formed the basis of the IPCC’s Third Assessment Report (TAR) published the same year and were also used for the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) published in 2007. In reality, the scenarios are thought exercises. In the IPCC’s words:

Future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are the product of very complex dynamic systems, determined by driving forces such as demographic development, socio-economic development, and technological change. Their future evolution is highly uncertain. Scenarios are alternative images of how the future might unfold and are an appropriate tool with which to analyse how driving forces may influence future emission outcomes and to assess the associated uncertainties.

Indeed, the IPCC is so keen to disabuse us of the idea that the scenarios have any objective probability that they use the term ‘storylines’ (hence the title of this post):

Four different narrative storylines were developed to describe consistently the relationships between emission driving forces and their evolution and add context for the scenario quantification. Each storyline represents different demographic, social, economic, technological, and environmental developments, which may be viewed positively by some people and negatively by others.

The scenarios cover a wide range of the main demographic, economic, and technological driving forces of GHG and sulfur emissions2 and are representative of the literature. Each scenario represents a specific quantitative interpretation of one of four storylines. All the scenarios based on the same storyline constitute a scenario “family”.

If you are not familiar with the the IPCC’s scenario categories, then the ‘A’ scenarios are broadly fast growth while ‘B’ ones sacrifice some growth for environmental sustainability. Likewise the ‘1’ refers to a converging world, while ‘2’ sees lots of different developmental paths. This gives a matrix of four major families (or ‘storylines’ to use the IPCC’s wording) as depicted by the image below:

Simplistically, A1 is close to what we have seen over the last decade: the triumph of the so called Washington consensus model of rapid industrialisation, free markets and open borders; global capitalism reins supreme, and citizen-consumers realise their personal dreams through shopping at the mall. B1, by contrast, would be something like a sustainable nirvana: perhaps E.F. Schumacher’s ‘Small is Beautiful’ but with rich countries making sacrifices to lift up the living standards of poorer countries in the name of equity and fairness.

The four storylines are then further subdivided into more scenarios. Branching out from A1 are the three scenarios A1FI, A1B and A1T. The first is a fossil fuel intensive growth scenario, the second a balanced fossil fuel/renewable scenario and the last a renewables heavy scenario.

These divisions are then subdivided yet again to produce a grand total of 40 scenarios. Note that the designation HS means that all these particular scenarios share “harmonized” assumptions on global population, gross world product, and final energy. With the OS designation, such assumptions are relaxed within a particular model.

After that quick tour of the IPCC emissions scenario methodology, let’s return to the Met Office’s choice of the A1B scenario to be the basis of its climate impact analysis. Before we do, just note again that the IPCC bent over backwards not to emphasise one scenario when its report was issued back in 2000:

No judgment is offered in this Report as to the preference for any of the scenarios and they are not assigned probabilities of occurrence, neither must they be interpreted as policy recommendations.

In other words, you choose your scenario at your own peril. The report, however, does gives us some metrics to assess how particular scenarios are fairing as the years go by. The chart below shows the A1 (dash for global growth) emission scenarios. Rather counterintuitively, A1B (the balanced technology scenario) is initially a higher CO2 emitting scenario than A1FI (the fossil fuel intensive scenario). This is purely because of the particular models chosen for each scenario.

More important, the A1FI (the top dotted line) and A1B (the thick line) scenarios part company around 2020, with CO2 emission levelling off for the latter as wind, solar and such like comes on stream in mass. Looking at the predicted CO2 emission in 2050, we can see the divergence quite starkly in the table below (click for larger image).

In a similar manner, the table below (again click for larger image) shows an emerging difference between A1FI and A1B with respect to the reliance on coal and introduction of zero carbon renewables between 2020 and 2050:

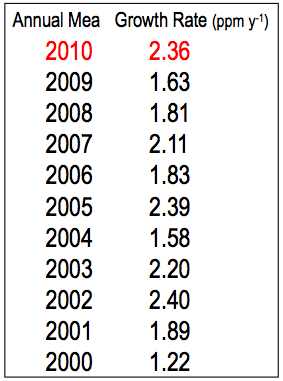

So which path is more realistic? A1B or A1FI? Over the very near term, the two paths see nearly identical emissions, but it is worth just checking to see how actual emissions have been trending vis-a-vis the scenario paths projected by the IPCC back in 2000. The chart below is taken from a presentation by the Met Office’s Richard Betts at the ‘4 Degrees and Beyond‘ climate change conference held at Oxford University. If we update the chart with the advance estimate fossil fuel CO2 emission number for 2010, which is 9.1 giga tonnes of carbon, we can see that we are currently trending along the top of the IPCC’s overall band, but close to the A1B path.

Please note though that A1B in its early years is not really a ‘balanced technology’ path as the renewables build-out has yet to take place. And, as noted before, because of some idiosyncrasies between the A1B and A1FI models, we are currently above the fossil fuel intensive A1FI path.

Against this background, fossil fuel emissions to date don’t really help us much in deciding whether we will end up following the A1B balanced technology path or the A1FI fossil fuel intensive path.

The next question is whether we can calibrate the IPCC scenarios by using the highly detailed International Energy Agency (IEA) scenarios as presented each year in their flagship World Energy Outlook report (which I recently posted on here). The IEA has three main emission scenarios: the 450 Scenario, New Policies Scenario and Current Policies Scenario. The 450 Scenario is a thought exercise on what is needed to be done to keep the atmospheric concentration of CO2 below 450 parts per million. Unfortunately, renewable infrastructure build is not even coming close to this scenario path, so we can put it to one side.

The Current Policies Scenario is defined as follows:

WEO-2011 also presents updated projections for the Current Policies Scenario to show how the future might look on the basis of the perpetuation, without change, of the government policies and measures that had been enacted or adopted by mid-2011.

Note this includes policies that had been adopted but not executed as, for example, China’s 12th Five-Year Plan, which includes energy intensity targets.

By contrast, the New Policies Scenario includes a broader wish list of policies that countries have flagged but not necessarily done anything about:

The New Policies Scenario incorporates the broad policy commitments and plans that have been announced by countries around the world to tackle climate energy insecurity, climate change and local pollution, and other pressing energy related challenges, even where specific measures to implement these commitments have yet to be announced.

Keeping these definitions in mind, the IEA’s CO2 emissions projections under different scenarios go out as far as 2035. In that year, the IEA sees 36.4 giga tonnes (Gt) of CO2 being emitted under the New Policies Scenario and 43.3 Gt of CO2 under the Current Policies Scenario (under the 45o Scenario, emissions would be only 21.6 Gt, around a 40% fall from the 2009 level of 28.8 Gt of CO2). By contrast, the two IPCC scenarios, A1B and A1FI, have CO2 emissions moving above 40 Gt by 2020 (note to convert carbon emissions to CO2 emissions we have to multiply by 3.67), so in the early decades they are both high growth.

By 2035, the A1FI scenario is accelerating away from the A1B scenario, with emissions that year around 66 Gt of CO2 for the former against 55 Gt for the latter. The worst case IEA Current Policies Scenario has 43.3 Gt for that year.

The conclusion we can draw this far is that the selection of the A1B scenario by the Met Office for their climate impact study looks reasonable when we look out over the foreseeable time frame of 2011-2035 as covered by the IEA. However, as we go further into the future, is does become more of a ‘story’.

The IPCC sees emissions peaking under A1B at around 60 Gt somewhere around 2050, which is about double the current level of annual fossil fuel emissions. Others are less sanguine. Ross Garnaut, the well-know Australian economist published a paper (here) that suggests emission growth rates will outstrip even the IPCC’s A1FI scenario:

Accordingly, A1B could be viewed as quite conservative near term (emission overshoots unlikely) but quite aggressive long term (emission overshoots likely). In short, we would need to base our climate impact studies on a more negative emissions scenario if we concur with Garnaut’s observations that 1) world GDP growth rates have continued to surprise on the upside and are likely to continue to do so and 2) key countries like China, India and Indonesia are being forced into an ever greater reliance on coal to meet their increasing energy needs, and will continue to do so.

At the same time, many of the trumpeted new technology hydrocarbon sources such as shale gas, shale oil and tar sands are not carbon emission friendly. They also suffer from a particular Peak Oil community concern: we are having to use ever-larger amounts of energy to extract a given amount of energy as the easily accessible sources have become exhausted.

Personally, I think the Met Office would be wise to tell two stories based on the IEA’s Current Policies Scenario and one with the New Policies Scenario but with the latter extrapolated out for a world with high economic growth. Policy makers need an understanding of how bad things could get from a climate impacts perspective, and the use of A1B alone does not provide this. Stories are wonderful things, but they can sometimes be misleading—and ultimately dangerous—as well.