Not long ago, the study of human collapse and extinction was the preserve of cranks (or Hollywood). True, a few maverick scholars have taken on the topic, Joseph Tainter and his book “The Collapse of Complex Societies” springs to mind. Yet little academic infrastructure existed to give collapse studies depth. But just as with happiness studies, another topic covered by this blog, the situation has now changed.

In the UK, our two oldest universities, Oxford and Cambridge, have both set up institutes that probe into the greatest risks faced by mankind. In Oxford, we have the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI), and in Cambridge the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER). To get a taste of the FHI and its founder Nick Bostrom I recommend you read this in-depth article by Ross Andersen of the magazine Aeon here.

Like this blog, Bostrom’s principal concern is risk; that is, the probability that an event will occur combined with the impact should that event occur.

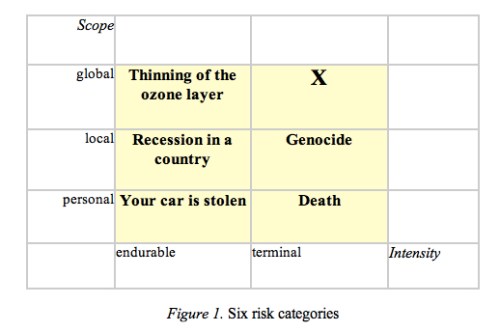

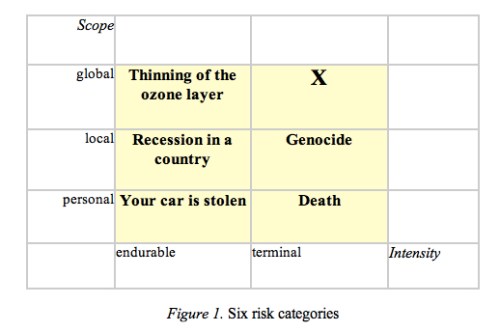

However, Bostrom extends this concept to take in scope: whether a particular risk is limited to a locality or whether it is all encompassing. This produces a risk matrix like this (source for the following analysis his paper here; click for larger image):

The X in the grid marks what Bostrom calls “existential risks”, which he defines thus:

A risk where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-orginating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential.

Bostrom then goes on to subdivide such existential risk into four categories:

Bangs: Intelligent life goes extinct suddenly due to accident or deliberate destruction.

Under this category we get traditional disaster movie scenarios of asteroid impact, nuclear holocaust, runaway climate change, naturally-occuring modern plague, bioterrorism, terminator-style super-intelligence and out-of-control nanobots.

Crunches: Society resets to a lower-level of technology and societal organisation.

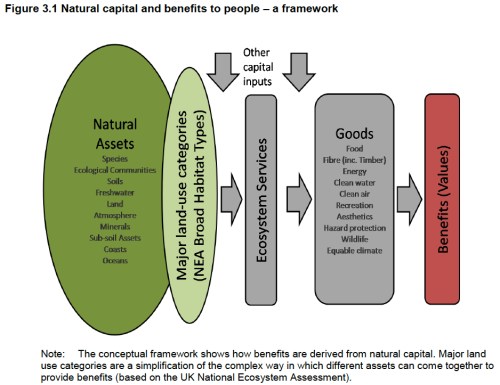

This includes bang-lite scenarios that don’t quite kill off intelligent life but rather just permanently cripple it. Crunches also cover resource depletion and ecological degradation whereby natural assets can no longer support a sophisticated society. Crunch could also come from political institutions failing to cope with the modern world–subsequent to which emergent totalitarian or authoritarian regimes take us backwards.

Shrieks: A postmodern society is obtained, but far below society’s potential or aspirations.

This is a rather nebulous category since the measuring stick of our potential is against something that we may not be able to understand–a reflection of Bostrom’s philosophical roots, perhaps.

Whimpers: Society develops but in so doing destroys what we value.

Under this scenario, we could pursue an evolutionary path that burns up our resources or we bump up against alien civilisations that out-compete us. Over the time scale that this blog looks at–the lifespan of our young–this existential threat can be ignored.

Building on many of Bostroms preoccupations, a joint report by FHI and the Global Challenges Foundation has just been published under the title “Global Challenges: 12 Risks That Threaten Human Civilisation”. The Executive Summary can be found here and the full report here. The report is again concerned with existential risks, but approaches this idea somewhat differently than Bostrom’s earlier work.

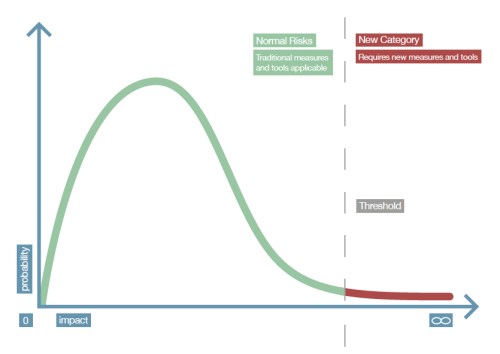

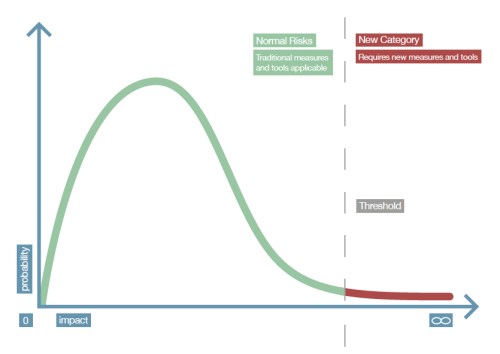

The focus of the report is on low probability but high impact events. The logic here is that low probability events are generally ignored by policy makers, but when such events occur, they could have catastrophic consequences. Accordingly, policy makers should be duty bound to plan for them. From a probability perspective, what we are talking about here is the often-ignored right tail of the probability distribution.

The 12 risks falling into the right tail of the distribution highlighted in the report are:

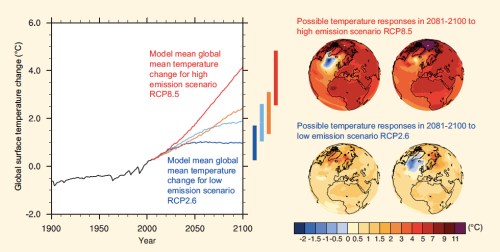

- Extreme climate change

- Nuclear war

- Global pandemic

- Ecological collapse

- Global system collapse

- Major asteroid impact

- Super volcano

- Synthetic biology

- Nanotechnology

- Artificial intelligence

- Unknown consequences (Rumsfeld’s unknown unknowns)

- Future bad global governance

As an aside, finance is one of the few disciplines that takes these tails seriously since they are the things that will blow you up (or make you a fortune). The industry often doesn’t get the tail-risk right (incentives often exist to ignore the tail) as the financial crisis of 2008 can attest. However, the emphasis is there. A lot of science ignores outcomes that go out more than two or three standard deviations; in finance, half your life is spent trying to analyse, quantify and prepare for such outcomes.

Returning to the Global Challenges report, the emphasis of the analysis is on dissecting tail risks, with the goal of provoking policy makers to consider them seriously. One of the most interesting proposals within the report if for a kind of existential risk early warning system, which I will look at in a separate blog post.

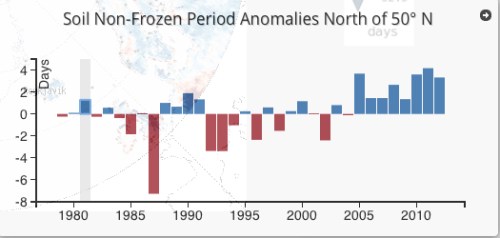

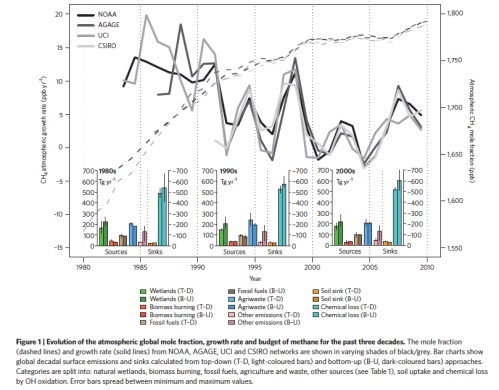

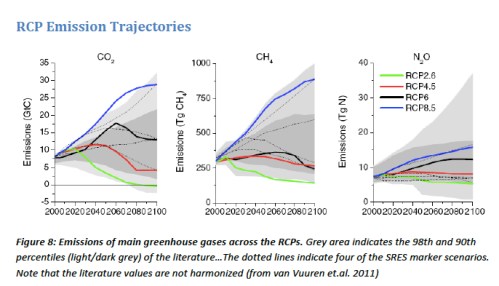

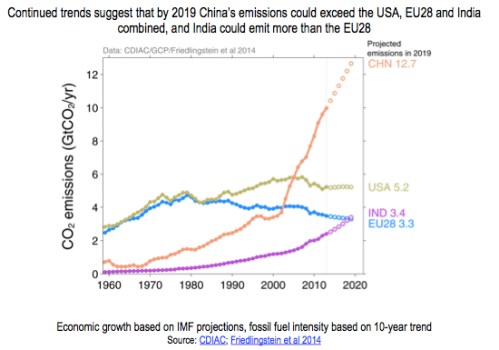

Finally, I will finish this post with a chart dealing with severe climate change (click for larger image or go to page 64 of the report), a risk that I hope will be at the centre of the upcoming COP 21 climate talks in Paris in December. The fact that our top universities are seriously studying such risks will, I hope, prevent them being seen as the preserve of cranks and disaster movies in future.