One of America’s greatest living authors Jonathan Franzen has a provocative article in The New Yorker arguing that the environmental movement’s infatuation with climate change has been detrimental to local environmental initiatives. I am a huge fan of Franzen: “The Corrections” and “Freedom” are two of my favourites books. Yet I find his analysis muddled. In fact, I disagree with almost everything he says.

Franzen presents the ‘wicked problem’ of climate change as almost insurmountable.

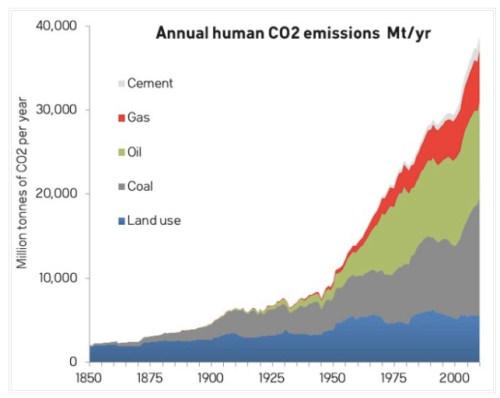

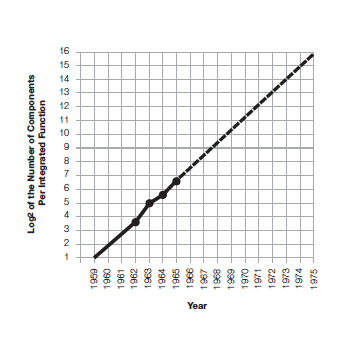

Climate change shares many attributes of the economic system that’s accelerating it. Like capitalism, it is transnational, unpredictably disruptive, self-compounding, and inescapable. It defies individual resistance, creates big winners and big losers, and tends toward global monoculture—the extinction of difference at the species level, a monoculture of agenda at the institutional level. It also meshes nicely with the tech industry, by fostering the idea that only tech, whether through the efficiencies of Uber or some masterstroke of geoengineering, can solve the problem of greenhouse-gas emissions. As a narrative, climate change is almost as simple as “Markets are efficient.” The story can be told in fewer than a hundred and forty characters: We’re taking carbon that used to be sequestered and putting it in the atmosphere, and unless we stop we’re fucked.

Against this background, Franzen believes that the concerned citizen is being bounced into caring about only one true environmental ill.

The question is whether everyone who cares about the environment is obliged to make climate the overriding priority. Does it make any practical or moral sense, when the lives and the livelihoods of millions of people are at risk, to care about a few thousand warblers colliding with a stadium?

And this is a planetary ill they can do nothing about.

To answer the question, it’s important to acknowledge that drastic planetary overheating is a done deal. Even in the nations most threatened by flooding or drought, even in the countries most virtuously committed to alternative energy sources, no head of state has ever made a commitment to leaving any carbon in the ground. Without such a commitment, “alternative” merely means “additional”—postponement of human catastrophe, not prevention. The Earth as we now know it resembles a patient whose terminal cancer we can choose to treat either with disfiguring aggression or with palliation and sympathy. We can dam every river and blight every landscape with biofuel agriculture, solar farms, and wind turbines, to buy some extra years of moderated warming. Or we can settle for a shorter life of higher quality, protecting the areas where wild animals and plants are hanging on, at the cost of slightly hastening the human catastrophe.

Indeed, I think his answer over how much emphasis we should place on climate change is wrong on many levels. First, I don’t see a trade-off. Humanity doesn’t have a finite budget of morality. If I am a good father, does that mean I have no choice but to beat my wife? In reality, those individuals campaigning against climate change are also likely to be the ones doing grass roots environmental activity. Continue reading